The United States’ reputation as an exemplar of democracy appears to be eroding.

In a poll taken earlier this year, almost three-quarters of U.S. respondents agreed that the country’s democracy “used to be a good example for other countries to follow, but has not been in recent years.” People elsewhere appear to share that sentiment. The majority of poll respondents in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan and South Korea also agreed with the statement.

More than 60 percent of U.S. respondents in another poll, from December 2023, believe that democracy in America is at risk depending on who wins the upcoming presidential election. Republican respondents see Democratic candidates as threatening the system and vice versa.

Now voters face the looming specter of the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, in which supporters of former President Donald Trump attempted to halt the certification of the 2020 election. Echoes of that event have many questioning whether this year’s election on November 5 will be free, fair and result in a peaceful transition of power.

A prominent metric that political scientists look to called Varieties of Democracy, or V-Dem — which hinges on the notion of free and fair elections — shows a slight dip in the health of U.S. democracy over the last decade (SN: 11/4/16).

Political scientists using that tool disagree over how to interpret that decline. Yet catching democratic erosion early is key to righting the course, says political scientist Rachel Beatty Riedl of Cornell University. “It’s really important to pay attention to those tiny dips.”

To understand the state of U.S. democracy, Science News went to experts with these five questions.

How do political scientists define and measure democracy?

Political scientists have long debated whether democracy is a matter of kind — a country is either a democracy or not — or a matter of degree.

Some 30 years ago, political scientist Adam Przeworski of New York University argued democracy exists when an incumbent government peacefully cedes power to the winning party following a loss at the polls.

“Democracy is a system in which [sitting] governments lose elections,” Przeworski says.

The simplicity of this binary definition allows for ease of measurement, as elections and their aftermath are readily observable. And this litmus test has endured. “It actually works well most of the time,” says Daniel Pemstein, a political scientist at North Dakota State University in Fargo.

But Przeworski’s test has limitations. Even when he introduced his measure in the 1990s, he had trouble classifying some countries — Botswana, for instance. “Botswana was and still is a country in which there’s relative freedom, freedom of the press, freedom of the unions. There are regular elections. Elections are never questioned by any observers, and yet the same party always wins,” Przeworski says. “So there was no way for us to tell what would happen if they lose. Would they accept the defeat, or would they not accept the defeat?”

Today, Przeworski’s measure shows that such hard-to-classify countries are increasing in number, which he suspects is due to a global trend away from democracy. But, he acknowledges, such small shifts are hard to capture with a binary measure.

How do you measure changes in democratic systems?

Many political scientists rely on metrics that treat democracy as existing along a continuum. The V-Dem project allows researchers and policy makers to evaluate a country’s system of governance along several dimensions, including level of inequality, whether citizens feel heard, and the presence and strength of systems of checks and balances.

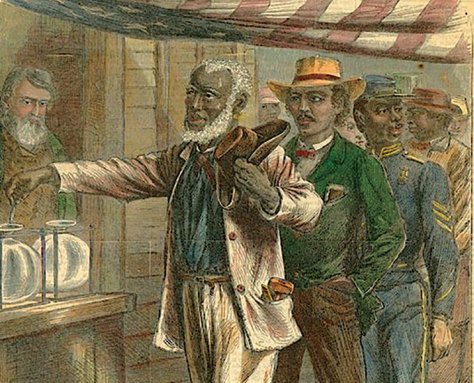

All those measures build from electoral democracy, says Michael Coppedge of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and a principal investigator for the project. V-Dem’s electoral democracy index focuses on the election period, including free and fair elections and other conditions surrounding the event, such as freedom of the press, respect for civil liberties, the right to organize and broad suffrage.

The more stringent and widely used V-Dem index of “liberal democracy” includes those factors and adds a close look at the years between elections, particularly a country’s system of checks and balances.

The system used by V-Dem to measure the health of democracy involves some subjectivity. Political scientists in countries around the world provide ratings for questions about governance, such as those pertaining to election violence and interference, executive respect for the constitution and impartiality among public officials. Their responses range from 0 for the worst behavior and up to 5 for the best. V-Dem researchers then take those responses to calculate scores, ranging from 0 to 1 (most democratic), for each index it tracks, including electoral and liberal democracy.

The political scientists don’t have to explain the rationale behind each rating, but analysts can look at which scores in the questionnaire have fluctuated over time to get a sense of their thought process, Coppedge says. “Our data is very good for tracking changes within countries over time.”

In the United States, the liberal democracy score has been on a marked upward trend since 1900, the first year in the index. But scores have recently dipped — from 0.85 in 2015 to 0.77 in 2023. The decline in scores is linked to survey responses related to violence around the time of elections, perceptions that opposition parties cannot exercise oversight over the ruling party, and weakened checks and balances. Coppedge cites several events over the last few years that could help explain what the expert raters were thinking, including efforts in some states to prevent felons from voting even after they have completed their sentences and partisan efforts to block Supreme Court nominees.

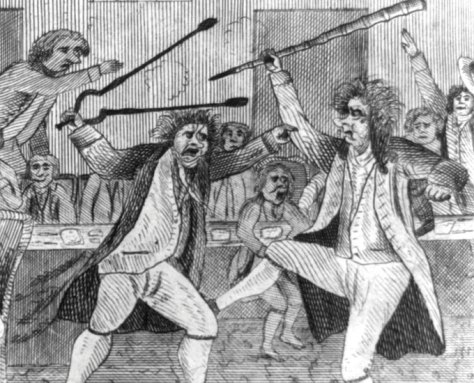

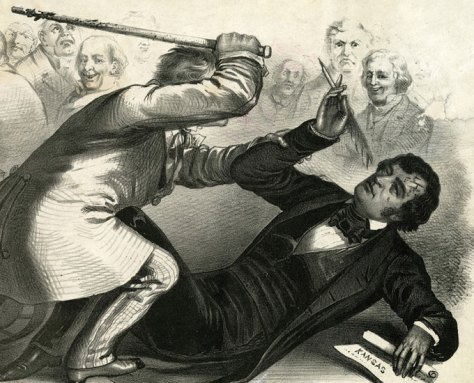

Many political scientists view the violent events of January 6, 2021, as particularly troubling. On that day, Trump supporters who refused to accept President Joe Biden’s November victory stormed the Capitol to try to overturn the election results. “That’s a pretty obvious effort to subvert democracy,” Coppedge says.

How troubling is the dip in the U.S. democracy score?

The U.S. score on liberal democracy remains on par with countries like the United Kingdom, which also scored 0.77 in 2023, and Canada, which scored 0.76. But researchers such as Riedl say that even small dips in scores warrant serious attention because pinpointing precisely when a country begins shifting toward autocracy is challenging yet key to thwarting further backsliding. And the U.S. dip is part of a larger global shift toward autocracy over the last decade, V-Dem researchers claimed in their 2024 annual report. More than 70 percent of the world’s population, or 5.7 billion people, lived in autocracies in 2023 compared with 50 percent in 2003, the team found.

Baseline electoral democracy scores provide further evidence of a global decline in democracy. In 2003, 11 countries were in the process of autocratizing. In 2023, that number nearly quadrupled to 42.

But some researchers question these findings. Earlier this year, a pair of political scientists found there is no global backsliding trend. Andrew Little of the University of California, Berkeley and Anne Meng of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville quantified purportedly objective measures of democracy (versus the more subjective V-Dem index), including Przeworski’s measure of incumbent losses at the polls, as well as executive constraints and attacks on the press.

There are over 200 countries in the world and, at any given time, some of them, such as Hungary and Venezuela today, will be undergoing democratic backsliding. But that does not make a trend, Meng and Little wrote in April in PS: Political Science & Politics. “The common claim that we are in a period of massive global democratic decline is not clearly supported by empirical evidence.”

Meng and Little refrain from commenting on whether the United States is in a period of democratic decline. But they speculate that intensive media coverage of the supposed decline could be biasing the judgment of experts, such as V-Dem’s raters. But Coppedge and his team say that they have found little to no evidence of such bias.

Regardless of how one calculates or interprets global trends, the odds of the United States turning into an autocracy are extremely low, political scientist Daniel Treisman of UCLA argued in 2023 in Comparative Political Studies. V-Dem data suggest that both wealth and duration protect a democratic country from reverting to autocracy. No democracy in the dataset that has survived for over 43 years has ever failed, Treisman notes.

Treisman’s work builds on political scientists’ long-standing observation that capitalism, and the wealth such a system generates, is linked to democracy. But trends over the last few decades suggest that the link might be weakening, Riedl and colleagues argued in a 2023 preprint in World Politics.

Treisman didn’t include countries that have democratized over the last several decades, and he took a narrow approach to understanding the process of autocratization, Riedl says. “Treisman and others tend to focus on full regime change, democratic death, which is indeed very rare.”

Subtler measures that look at the weakening of democratic systems paint a more nuanced picture. Riedl’s team analyzed more than 100 episodes of democratic erosion across all countries in the V-Dem dataset since 1990. Thirty-eight of the 202 countries in the dataset experienced statistically significant reductions in democracy scores. Roughly half of those countries exceeded wealth levels thought to protect against such erosion.

What factors play a role in destabilizing democracy?

Political scientists have typically focused on forces that stabilize democracies in capitalist societies, such as wealth, education and labor, Riedl says. But they have paid less attention to capitalism’s destabilizing forces, chiefly endemic inequality. That inequality, coupled with polarization — both a cause and effect of backsliding — helps promote populist leaders promising to make the system work for everyday people, regardless of whether the proposed solutions adhere to democratic principles, Riedl says. Such populist leaders may come to power through legitimate elections but then pursue autocratic agendas by weakening systems of checks and balances.

For instance, Hungary appeared to be a stable democracy during the 1990s and 2000s, with liberal democracy scores above 0.7. Those scores began plummeting when Viktor Orbán became prime minister in 2010, dropping to just over 0.3 by 2023. Orbán has spent years chipping away at the courts’ independence, seeking to put the judicial system under control of the ruling party, packing the courts with partisan judges and extending judicial term limits.

“Changing the composition of the courts is a really significant pathway to authoritarianism,” Riedl says.

In the United States, four factors could trigger democratic backsliding, political scientists Suzanne Mettler of Cornell University and Robert Lieberman of Johns Hopkins University wrote in March in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Those factors are polarization, conflicts over belonging, economic inequality and executive aggrandizement.

The January 2021 insurrection, in which all four factors converged for the first time in U.S. history, was a particularly troubling threat because it violates Przeworski’s basic tenet of peaceful transition of power as core to democracy, Mettler says. “You have to accept the outcome and let the winner govern. And if you get away from that, you just do not have democracy.”

What helps keep democracy strong?

Finding and utilizing points of resilience, such as the courts, legislatures or a vibrant independent press, are key to strengthening democracy, according to experts.

In Brazil, for instance, the courts determined that former President Jair Bolsonaro had abused his power when he claimed, without evidence, that the country’s election system was rigged ahead of his 2022 loss to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. In June 2023, justices blocked Bolsonaro from seeking re-election until 2030.

Even when voters believe checks and balances are weak, their voices, coupled with a robust media, can ward off threats, Riedl says. In 2023, she coauthored 15 in-depth case studies of countries showing signs of autocratization for the U.S. Agency for International Development.

South Korea, for instance, shows the need for constant vigilance. The country recovered from an autocratic turn in the last decade but continues to oscillate between democratic regression and recovery, according to the V-Dem project.

The country’s score went from 0.6 in 2014 to 0.8 a few years later due, in part, to intense media exposure and coverage of then-President Park Geun-hye’s central role in a massive corruption scandal. That reporting triggered months-long candlelight rallies demanding Park’s impeachment. The country’s independent National Assembly impeached Park in December 2016. In March 2017, the courts upheld the impeachment and forced Park out of office. Recent reports, though, show that the country’s scores are now back in the 0.6 range due to the current administration’s punishment of members of the previous presidential administration.

The United States has strong points of democratic resilience, Coppedge says. That includes powerful, independent media outlets and civic society organizations, intense competition between political parties, and public engagement at all levels in the process, whether it’s learning about candidates’ positions, supporting candidates through actions like canvassing and phone-banking and, most essential, voting.

“Institutions and government leaders,” Riedl says, “can be empowered to be agents of democracy when they are given that push from below.”

#U.S #democracy #decline #Heres #science

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org